With all the dog parks and specialty pet stores within one square mile, it’s hard to think that there was ever a time that Hoboken dogs weren’t held on pedestals by their owners and the local municipality. In the present day, Hoboken’s unique affinity for our pets reigns supreme. However, long ago in Hoboken, dogs didn’t always get the love and care that they deserve. When it comes to the history of dogs in Hoboken, it’s a long and storied timeline of the City’s relationship with dogs — which has waxed and waned over the last few centuries. Looking back at our relationship with the canine allows us to appreciate how dog-friendly Hoboken has become, especially since there was once an ordinance in Hoboken that said “all dogs found running in the city limits…shall be taken to the pound or killed.” Here’s an abbreviated timeline of the history of dogs in Hoboken, thanks in part to the Hoboken Historical Museum.

Lenape’s Best Friend: The Dog

Long before Europeans set foot in Hoboken, the land was inhabited by the Lenape Native Americans (previously referred to as the “Delaware Indians”). In fact, “Hoboken” is a Lenape name meaning “Land of the Tobacco Pipe,” as it’s believed the Lenape carved their pipes from Castle Point’s soft soapstone.

While some Native American tribes ate dogs — such as the Sioux or the Cheyenne — the Lenape did not. Interestingly, the dog was the only domesticated animal of the Lenape. Horses were introduced to the Americas by Europeans, and therefore the Lenape used dogs to haul materials. During the winter months, dogs were used for sledding and to cuddle with to fend off the blistering cold. Throughout the year, dogs protected the tribe and aided in tracking and hunting.

Read More: The 1st Forward Pass in Football Was Thrown in Hoboken

Hoboken Dogs in the Colonial + Industrial Eras

Hoboken’s colonial and industrial eras brought about modern problems of urbanization—overcrowding and disease. The unfortunate truth is that for much of the 19th Century, dogs were considered a vessel of pestilence, and often the target of ire by municipal authorities.

1850s: Bounty Payments on Dogs

Regular rabies scares arose in cities during summer months, and dogs were often targeted for culling. In the 1850s, New York City offered a bounty payment of 50 Cents per dog. Incredulously, “street boys” crossed the Hudson River for 5 cents, only to steal Hoboken dogs and deliver them to the East 31st Street Pound in Manhattan.

1869: Stray Dogs Ordinance

Hoboken’s Municipal Authorities were no kinder to dogs during that time. In 1869, Hoboken’s Mayor Hazen Kimball issued an ordinance empowering “any person…to slay canines running at large unmuzzled…Interference with the slayer will subject the interferer to a fine of $10.”

1885: Stevens’ Family Photo Boasts a Dog

That is not to say that the citizens of Hoboken hated dogs. Hoboken’s founding family, the Stevens Family, loved dogs — as evidenced by this 1885 photograph showcasing their main pup, front and center.

(Photo credit: Stevens Institute of Technology Archives)

1912: Hoboken Dog Lovers Fight Back

The many dog-lovers in town eventually assembled to fight back against the cruel municipality ordinances. By 1912, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (S.P.C.A.) called for a local “dogs’ court” to prevent the indiscriminate killing of dogs, as well as strict licensing and leashing laws. No “dogs’ court” was ever established, but licensing and leashing laws were enacted, along with an “assistant pound keeper” who was added to the city payroll at $75 a month; the S.P.C.A. would handle “dog confiscation” on its own. The following year, the S.P.C.A. captured over 1,600 dogs in Hoboken with only four dogs showing any sign of rabies.

1916: Dogs Carry Polio? A Scare

“Mad dog scares” continued to make headlines (fast forward to 2022, and we’re talking skunks and coyotes!), and in the summer of 1916, a new, unfounded fear gripped the East Coast — that dogs carried polio.

In reality, dogs can neither carry nor transfer polio. Still, frightened residents banned dogs from schoolyards and pet owners washed their dogs in a diluted solution of carbolic acid.

Hoboken Dogs in WWI

WWI was a turning point for dogs within the public’s imagination. At home during the war, police officers were incentivized to capture dogs with the grim justification that large dogs would make good gloves for soldiers — smaller dogs could be used to test gas for warfare against the Germans.

But on the European battlefront, soldiers developed a completely different appreciation for the pooches. Dogs were routinely used as mascots within the trenches, providing entertainment, companionship, and a keen nose to sniff out rats or other vermin thereby aiding the soldiers’ health and safety.

1919: Dogs Make the News

In August of 1919, both the Hudson Dispatch and the New York World excitedly reported on the “greatest collection of animals as mascots that have yet been brought to America on transport.” Newspapers routinely pictured soldiers carrying cute canines within their rucksacks.

1915: A Picture of Helen Stevens

Photographs further illustrate the love and affinity Hoboken residents held for their dogs during that time. A remarkably modern photo from 1915 shows how dearly Helen Ward Stevens (of the Stevens Family) cared for her dog.

(Photo credit: Stevens Institute of Technology Archives)

1920: Church Square Park Posing

In 1920, people posed at the southeast corner of Church Square Park with all their delightful doggies.

(Photo credit: Hoboken Historical Museum)

1922: An Honorable Dog Funeral — Albeit a Twist

In 1922, the dentist Arthur M. Hyde at 63 Newark St., photographed his late dog, Rex, with a casket, printed epitaph, $350 in flowers, and a hearse. However, this was also due to another unfortunate reality of dogs during that time. Arthur explained: “I ought to be willing to spend at least that sum, when you consider that Rex in his 16 years of life won 22 battles with other dogs. Altogether I won $800 in bets that I placed on my dog in dog fights.”

(Photo credit: Hoboken Historical Museum)

The years 1933 and 1934 illustrate Hoboken’s two vastly different attitudes toward dogs.

Hoboken’s 1933 Ruling

In 1933, the Jersey Journal highlighted the story of a “habitual drunkard,” a Hoboken woman sentenced to 15 days in the County Jail. She avoided incarceration when the judge learned her absence would abandon her two dogs without care: “She told the judge no one would take care of her pets if she were sent away. The woman’s plea touched the heart of the judge — he has a pet dog himself.” The judge argued that women often avoided jail because of their children and decided: “I’ll reconsider your sentence and place you on probation for six months. Now go home and take care of yourself and your dogs.”

Hoboken’s 1934 Ordinance

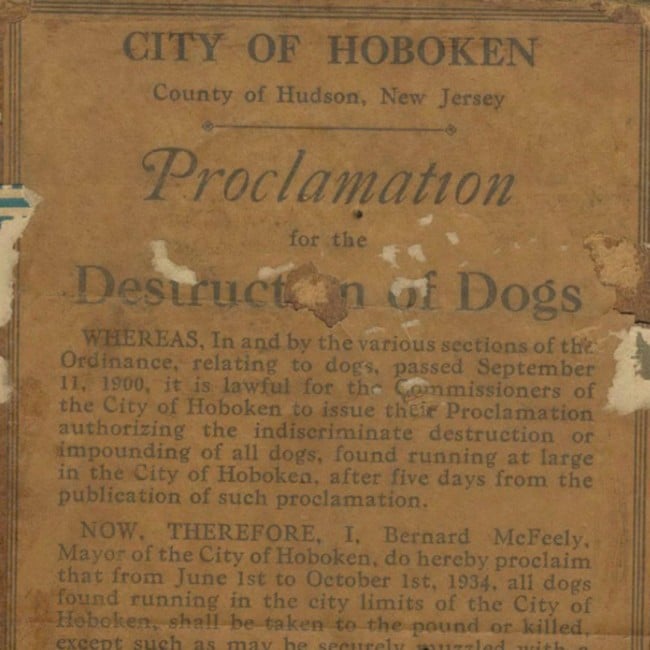

Meanwhile, the following year, in 1934, Mayor McFeely — the Hoboken Mayor famous for his rampant nepotism — issued a “Proclamation for the Destruction of Dogs.”

The ordinance stated “all dogs found running in the city limits…shall be taken to the pound or killed” and anyone obstructing such efforts would be fined up to $25.

Dogs in the 20th Century

June 1978: Dog Owners Fight Back

Over the course of the 20th Century, the dog-lovers won out. By June of 1978, the Jersey Journal reported that Hoboken’s animal warden “complained that his men have been threatened with knives and sticks when they try to pick up stray animals…In one case, the city sanitarian was pushed down a flight of steps while trying to confiscate a pet.”

1985: Dogs Make Hoboken Print

By 1985, the famous children’s author and illustrator Daniel Pinkwater (author of The Hoboken Chicken Emergency) published the book Jolly Roger: A Dog of Hoboken, about a legendary stray who became “King of the Dock Dogs.”

(Photo credit: Hoboken Historical Museum)

2000: Pup + Human Relationships Improve in Hoboken

In 2000, a small group of dog owners collected to “improve relations between local dog owners, the City, and the Hoboken community at large.” They formed the Hoboken Dog Association (HDA) which — according to their Facebook page — has worked with city representatives “to improve the city dog runs, modify existing dog regulations, and educate about responsible dog ownership in an urban environment.”

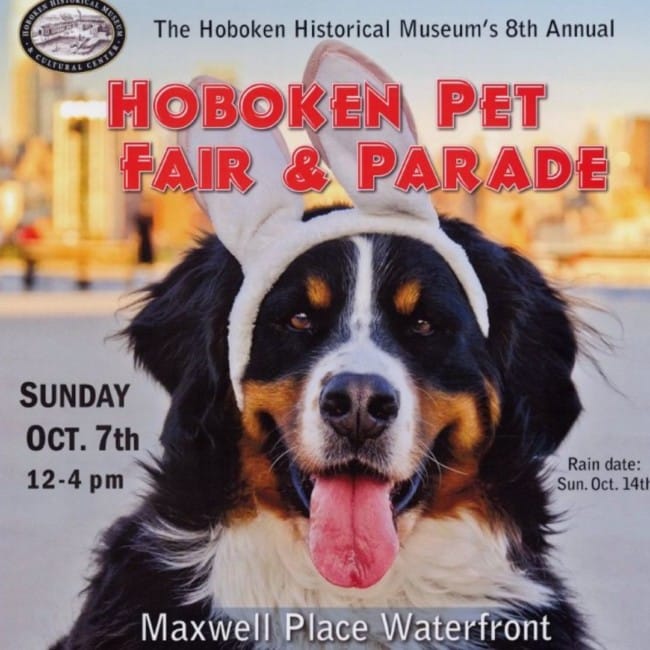

2003-2012: Hoboken Hosts a ‘Pet Parade’

From 2003 until 2012, the Hoboken Historical Museum held an annual “Pet Parade,” but the event was unfortunately discontinued due to insurance liabilities.

2019: A Dog Poop Ordinance

While the last two decades have proven that having a dog Instagram account or buying your dog a birthday treat isn’t out of the ordinary, there has been a rise in dog poop found around the area. To combat this, the most recent ordinances involving dogs in 2019:

Leash Your Dog: Dogs on sidewalks, streets, and in parks must be on a leash, except when in a dog run.

Pick Up The Poop: Failing to pick up after your pet on sidewalks, streets, and in parks is punishable by a fine of up to $2,000.

License Your Pet: All dogs in Hoboken MUST be licensed by law. Learn more at hobokennj.gov/petlicense.

(Photo credit: Hoboken Historical Museum)

After this brief history of Hoboken’s dog devotion — we’d be remiss if we didn’t include two of Hoboken’s most famous canines.

The Wealthiest Dog on the Waterfront: Blackie

One of Hoboken’s most famous and beloved dogs “ruled the waterfront with an iron paw.” Blackie, a black Labrador, came to Hoboken in 1944 as a “Belgian war-time refugee” across the Red Star freighter and she “adopted” the entire working force of the Holland-America Dock.

(Photo credit: Hoboken Historical Museum)

The 1949 Holland-America Line’s newsletter describes Blackie as the “Queen and undisputed ruler of the 75 cats around the piers between 4th and 5th St.”

Each morning, Blackie enjoyed breakfast — a coffee and a doughnut — with the head stevedore. At lunchtime, she hunted the head cooper, whose wife packed a daily lunch for the dog for four years. For supper, Blackie was the nightly guest of “Sparky” (the Holland-America Line’s harbor master) at his home at 103 4th Street.

(Photo credit: Hoboken Historical Museum)

Blackie not only had friends, but she was also the wealthiest dog on the waterfront — with a $75 bank account in her name. When she’d become ill, pier workers took up a collection to send her to a veterinarian. When the doctor’s fee had been paid, $75 still remained, so it was deposited in Blackie’s name against any further emergencies.

One time Blackie tried to separate two quarreling seamen brawling outside the Holland America Pier. A complaint was filed with the police that she had tried to bite one of the sailors, and a dog warden was sent over to take Blackie into custody — but the 300 stevedores “set the dog warden right” and Blackie stayed. She was buried near the 5th Street Pier (currently between Pier C and Stevens Park).

See More: A Tour of Noteworthy Historical Homes in Essex County

Taps: the Child-Saving Dog

Taps, a Dalmatian/Pointer mix, was adopted by Hoboken’s Engine Co. 5 when he was just 4 weeks old.

Soon, Taps joined Engine Co. 5 in fire rescues, even saving a child’s life by finding a boy trapped within the bathroom of a burning building. Even the most hardened, veteran firefighters wept when Taps was euthanized at a Jersey City animal clinic after his diagnosis of liver cancer.

A procession of six fire trucks illuminated their headlights in a vigil which returned Taps to the Hoboken firehouse where his pine casket was placed on the back of a pumper.

His body was buried in Church Square Park beneath the statue dedicated to volunteer firefighters. Fire Captain Edward Scharneck summed it up best when he said, “He got a real hero’s funeral.”

Editors note: Much of the information in this article came from a Hoboken Historical Museum exhibit which was turned into a book: City Animals: A History of Our Changing Relationship with Other Hoboken Residents (2004) by Holly Metz.