Taking the PATH train or hopping a ferry are arguably the easiest forms of transportation that Hudson County residents can use to get into NYC for a workday commute or a weekend visit. A trip through the Holland Tunnel requires paying the toll, difficult parking on the other side, heavy traffic with no right turns on red, pedestrians everywhere, traffic weaving bikes… it’s certainly a hassle. Though when driving needs do arise, the Holland Tunnel is right here to get us where we need to be. Read on to learn all about the history of the Holland Tunnel.

A Very Necessary Tunnel

In January of 1918, due to record cold temperatures, the portion of the Hudson River surrounding New York City froze. For weeks, boat traffic between New Jersey and New York City was impossible. There were serious coal and food shortages on the east side of the Hudson as the majority of the goods that kept NYC going were usually shipped in via the Jersey City waterfront. After that very difficult winter, the effort to build what we now call the Holland Tunnel became a priority.

Prior to the completion of the Holland Tunnel, car ferries transported more than 20,000 vehicles across the Hudson each day. Plans for what is now the George Washington Bridge had been discussed and debated since 1906, but the New Jersey and New York legislatures didn’t put that project to a vote until 1925, and construction for the GWB only started in 1927. The first segment of Weehawken’s Lincoln Tunnel wouldn’t open until 1937, making the Holland Tunnel’s 1927 opening unique and essential.

Read More: A Look Into the History of Ellis Island + Why You Should Visit

An Engineering Wonder

The Holland Tunnel was constructed between 1920 and 1924 with an official opening in 1927, and upon completion it became the largest vehicular underwater tunnel in the Americas. 36-year-old Harvard-educated Clifford Milburn Holland was made chief engineer of what was then called the Hudson River Vehicular Tunnel project. Once completed, the two tubes that run its length — for vehicles running in opposite directions — would span over 8,500 feet. At the tunnel’s deepest point, it is 93.4 feet underwater.

Construction started simultaneously on both sides of the river. Precise measurements ensured that each tube lined up perfectly to meet in the middle. Tunnel workers (affectionately known as ‘sandhogs’) dug through the mud by pneumatically pushing cylindrical shields through the river bottom. Those shields held back the earth, making way for construction of the thick tunnel walls, built of cast iron rings filled with concrete.

The name ‘sandhogs’ was first given to the men who were working on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1872. These urban mining crews dug the underground infrastructure of the ever-growing, densely-populated region. Sandhogs were often born into the work, with multiple generations working side-by-side. Their stories of tragedy, resilience, community, and pride in building everything beneath us — from sewers to subways — is a worthwhile topic for the curious to pursue. Between 1921 and 1924, 13 sandhogs died building the Holland Tunnel.

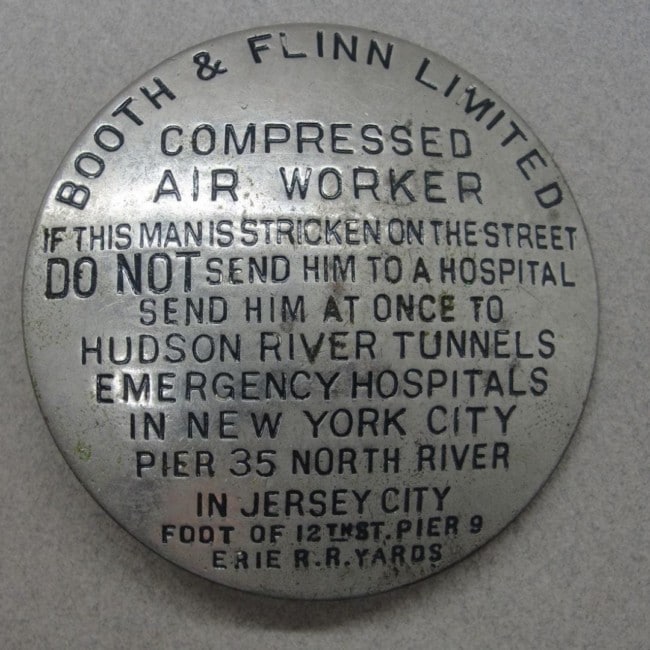

Tunnel workers faced multiple dangers, including the loathsome bends. Air pressure inside the tunnels had to be constantly monitored to match the pressure of the water outside so that river water wouldn’t flood the tunnel and drown the workers. The impact of that excessive air pressure pushed the workers to strike, seeking higher pay and a reduction of air pressure from 21 PSI to 18 PSI. The workers were worried about getting decompression sickness, which is caused by the drastic change from high to low pressure that workers would experience when they left the tunnel to go back outside.

In 1924, Clifford Holland died of a heart attack brought on, it was said, by the stress of the tunnel project. His death came one day before the final charge of dynamite that was used to clear the way to connect the two tubes that formed the east and westbound tunnels. 16 days later, on November 12th, the now-renamed Holland Tunnel would open to more than 20,000 pedestrians who walked the length of it.

Those Art Deco Towers

Four sand-colored brick ventilation buildings act as the lungs for the tunnels. Two 10-story towers rise out of the Hudson on the Jersey City side and two rise out in New York. Fresh air enters holes in the bottom of the shafts and the exhaust rises through the tunnels and exits through vents. 84 powerful fans replace the air in the tunnel every 90 seconds. Each of these electric fans is 8 feet in diameter. The polluted air is drawn off through a duct in the roof of the tube with the aid of suction fans. Designed by Norwegian architect Erling Owre, the exhaust towers, like the beloved Jersey City Powerhouse, are something between a work of engineering and architecture.

The tunnel was considered a notable engineering achievement in large part because it solved the problem of ventilating a long tunnel endlessly full of exhaust. Imagine the carbon monoxide producing soot from all those mid-century high-polluting automobiles. Of course, the drivers inside the cars were likely smoking cigarettes with their windows up anyway.

The massive tunnel ventilation towers were put to the test on the morning of May 13th, 1949. A truck carrying eighty 55-gallon drums of carbon disulfide ignited from the vapors after entering the southern tube at the New Jersey side. Nine other vehicles caught fire and several secondary fires followed after that. With 125 vehicles stuck in the tube, an evacuation operation accompanied the firefight. The ventilation system was turned to full exhaust, extracting the smoke remarkably well. New Jersey and New York firefighters made their way to each other, succeeding in extinguishing the fires. One firefighter was killed and 66 civilians required hospitalization. A 1996 Sylvester Stallone movie, Daylight, was loosely based on the incident.

See More: The Long Legacy of Oysters in North Jersey

A Tunnel Toll-Taker’s Lament

Today, more than 100,000 vehicles pass through the Holland Tunnel on a given day. The toll to enter the tunnel heading east into NYC through the southern tube costs a whopping $16 (a bit less with E-ZPass), but leaving The City is free. Initially, the toll was the same both ways — 50¢ a car, 25¢ for motorcycles.

The November 1928 issue of Poetry Magazine featured Daniel Henderson’s playful imagining of the boredom that tollbooth workers might experience while stationed outside the Holland Tunnel, entitled, Coin Watcher: Hudson Tubes It’s incredible to think about how far we’ve come since this nearly century-old poem was published — and while the trickle of pennies, dimes, and nickels that Daniel references in his poem may now be a thing of the past, the tunnel’s function and importance to New Jersey locals remain unchanged.