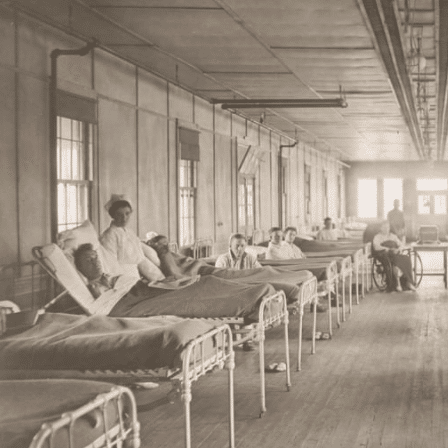

Across the country, we’re hearing that this time of history with COVID-19 has been the worst public health pandemic the globe has seen since the Spanish Flu. In 1918, like today, people across the country and world were sheltering in home due to the Spanish Flu — a previous pandemic seen by the world. The flu infected 500 million people, which was one-third of the world’s population at the time, and the CDC called it the most severe pandemic in recent history. It’s no secret that history repeats itself, meaning that a great way to handle the future is to look to the past. That being said, we’re taking a deep dive to discover what Hudson County was like during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

View this post on Instagram

In the U.S.

In the United States, about 675,000 people lost their lives {of an estimated 50 million fatalities worldwide}. History.com writes that the disease came in two waves, with those who fell ill in the first wave reporting “typical flu symptoms as chills, fever, and fatigue,” and the second wave of sufferers reported that “their skin [was] turning blue and their lungs [were] filling with fluid that caused them to suffocate.”

Back then, as National Geographic reports, New York began its quarantine early —11 days before the death rate spiked. It even had the lowest death rate on the Eastern Seaboard. New Jersey, though, wasn’t so lucky. In September of 1918 alone, a Department of Health report counted 222 deaths from influenza in the state, according to NorthJersey.com. By the next month, the mortality numbers had skyrocketed, with the pandemic being attributed to the loss of 8,477 lives.

Read More: Latest Jersey City + Hoboken COVID-19 Updates

The Pandemic in NJ

The first case in the state occurred in South Jersey when Montclair resident and chief of the medical service in the army, Martin Synnott, fell ill on a Fort Dix base. The virus then swept through the base, killing 862 people in September and October of 1918 alone.

As a result, all of New Jersey went into quarantine from September to December of 1918, though it would be lifted in November because of a slower death rate. But, Fort Dix wasn’t the only military base affected. The Camp Merritt Military Base in Cresskill was, in World War I, a place where troops gathered to be sent to Western Europe on boats that left from Hoboken. The result of these large group gatherings ultimately became a tragedy — 578 people, including 557 enlisted men, succumbed to the virus and died. Today, there’s a 66-foot tall structure, called the Camp Merritt Memorial, that stands in what was once the center of the base and marks the names of each person who passed away.

On a Local Level

Newark had a rate of 533 deaths per 100,000 cases after 24 weeks of the pandemic, which was among the highest rates in the country. The city quickly became a ghost town and closed everything down, but from September to December, it still saw 2,100 deaths when influenza was at its peak in Newark.

In September 1918, E.B. Walden, the owner of the Bergen Daily News, addressed town’s Board of Health at a meeting. He said he “understood the disease was infectious as well as contagious and that it would be wise to keep in touch with the situation.” On October 8th of the same year, Hackensack’s mayor Milton Demarest announced the closure of “all churches, theaters, moving picture houses, dance halls, pool rooms, lodge rooms, saloons, soda fountains, and other places.” Less than three weeks later, on October 28th, the Bergen Evening Record reported that the Hackensack Hospital recorded 1,466 influenza cases, 96 pneumonia cases, and 85 deaths.

The Jersey Journal also ran precautionary articles, advising the public about ways to avoid the spread of the deadly virus. The Department of Public Affairs ran notices in the paper stating that the disease was spread via contact — sneezing, coughing, and spitting were directly called out —and cleanliness, avoiding crowded common areas like churches, railway stations, and theaters were noted as ways to prevent the spread of the disease.

See More: What It’s Like to Fly During a Pandemic

In Hudson County

Jersey City also battled the Spanish Flu. The legendary mayor Frank Hague asked his medical director to look into dealing with the pandemic, which yielded some interesting results. “Signs were posted prohibiting spitting, and housewives were urged to peel or thoroughly scrub raw foods,” which people thought carried the virus they called “The Grippe.”

All of this was happening in the midst of another major historical event —WWI. In March of 1918, according to the Hoboken History Museum’s archives, military presence increased in Hoboken and many Chinese restaurants were given curfews, forcing many out of business. Women faced prostitution charges if they were out after dark and armistice was declared in November 1918. Celebration and mourning alike took place in Hoboken before the first soldier returned to the Mile Square on December 2nd, 1918, when the city was still in the clutches of The Grippe.

Making History

The pandemic lasted until the summer of 1919, when many who were infected passed away or developed immunity and life would eventually return to normal, with Hudson County and the country as a whole recovering from the massive economic and social loss the pandemic caused. As we see the world slowly reopen in the wake of COVID-19, we remember our neighbors and loved ones who lost their lives in the pandemic of 1918.

Check out Hoboken Girl’s new Job Board here!